Penny-Lynn Cookson

Special to The Lake Report

As time and space coalesce, how will we remember these COVID-19 days, weeks, months?

Will we despair of time lost in the absence of family and friends? Will we laugh at the memory of spontaneity that brought joy? Will we treasure the unexpected that altered our perceptions?

In isolation, did we become more open, more forgiving, more generous or more guarded and uncaring? Did we dream of love and places to see or feel nostalgia for homes and landscapes left long ago? Were we confused by our dreams and skewed reality? Did we describe what we were experiencing as “surreal”?

The Surrealist movement, championed by André Breton, Apollonaire and Magritte among others, came at a time of chaotic change. The 1910s had seen the horror and slaughter of the First World War and revolutions after which no one believed life as “normal” would ever return.

The 1920s brought strikes, the stock exchange crash, Prohibition, the jazz age, radio, cinema “talkies,” Einstein’s Nobel Prize for physics, Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, death on the streets of Ireland and Germany, and civil wars from Mexico to China.

The 1930s were no less dramatic as the capitalist west entered the worst depression ever. Civil war in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini were a foretaste of the fascism to come.

Elsewhere it was business as usual: exploitation in Africa, upheavals in South America, unrest in India, travel by sea, railways and air, Hollywood glamour and musicals to help everyone forget the mess. Into this time frame emerged Salvador Dali, the most famous and controversial Surrealist of them all, born in 1904 in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, and by 1934 an art world sensation.

Dali had studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, where his talent and technical prowess were apparent and where he considered his teachers inadequate to judge his work. Immersed in Cubism, Futurism and the avant-garde movements of Dadaism and Surrealism, he joined the Surrealists in Paris in 1929 as they shared his interest in releasing the creative powers of the unconscious mind and making the contradictions of dreams and reality an absolute reality.

He was profoundly influenced by Sigmund Freud’s research into dreams and sexuality, and his theories of how the unconscious can reveal latent desires and paranoia. Dali developed his “paranoic-critical” method of engaging in self-induced hallucinations to access the subconscious for artistic creativity and to systematize confusion and upend reality.

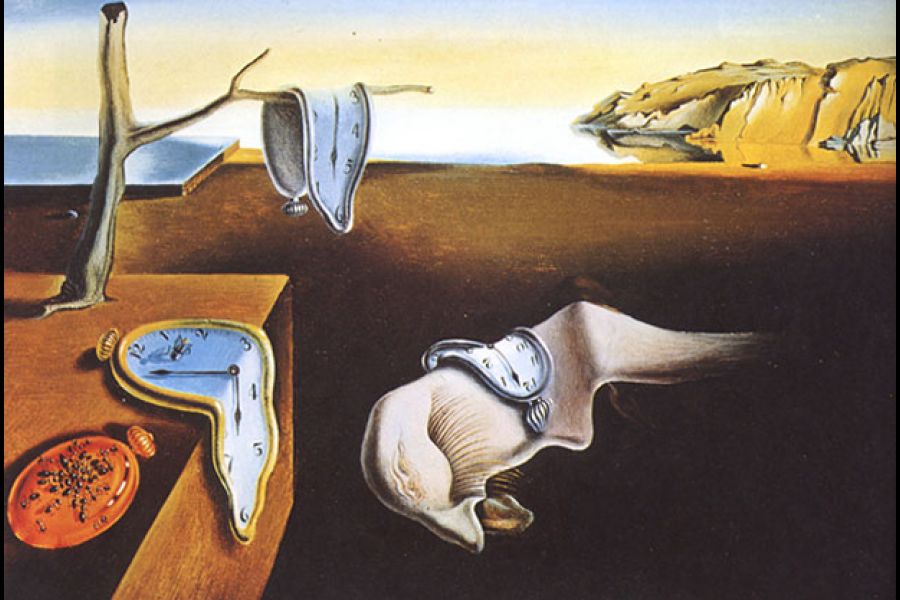

His “The Persistence of Memory” was exhibited to acclaim in Paris and the Wadsworth Athenaeum in 1931 and in 1933-34 in New York. Dali’s eccentric persona of bulging eyes, upturned thin Velasquez moustache, relentless self-promotion and admiration for American popular culture were as notable as his art. But the man was in earnest stating, “The difference between a madman and me is that I am not mad.”

In “The Persistence of Memory,” Dali combines hard and soft imagery. His out-of-place hard pocket watches morph into soft forms melting in the sun. An unconscious symbol of the relativity of space and time, the collapse of our ideas of a fixed cosmic order? Einstein’s theory of general relativity? “No,” said Dali, “nothing more than the soft, extravagant, solitary Camembert cheese of time.”

But the hands are set at 12.30, 6, 6:55 – a subjective past, present, future? One watch has a fly on it, symbolic of decay and time devouring itself. One facedown hard orange watch is covered with crawling ants, their hourglass-shaped bodies a reminder of human mortality and impermanence against a “sands of time” landscape.

A leafless olive tree with cut branches suggests the death of ancient wisdom in a time of war and unrest. The anthropomorphic form in the middle is a self- portrait in profile, one long lashed eye closed in sleep, tongue extending from the bony nose like a soft, plump snail, the enigmatic figure in dreams.

The craggy, golden cliffs of the Catalan Cap de Creus peninsula, the timelessness of the sea, the light on sky, shore and rocks synthesize home to Dali. His absolute realism gives us suspended time, relative not fixed.

Penny-Lynn Cookson is an art historian who taught at the University of Toronto for 10 years. She was also head of extension services at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Her upcoming virtual lecture series “Landscape and Memory” runs Aug. 4 to 25 at the Pumphouse Arts Centre. Registration is free.